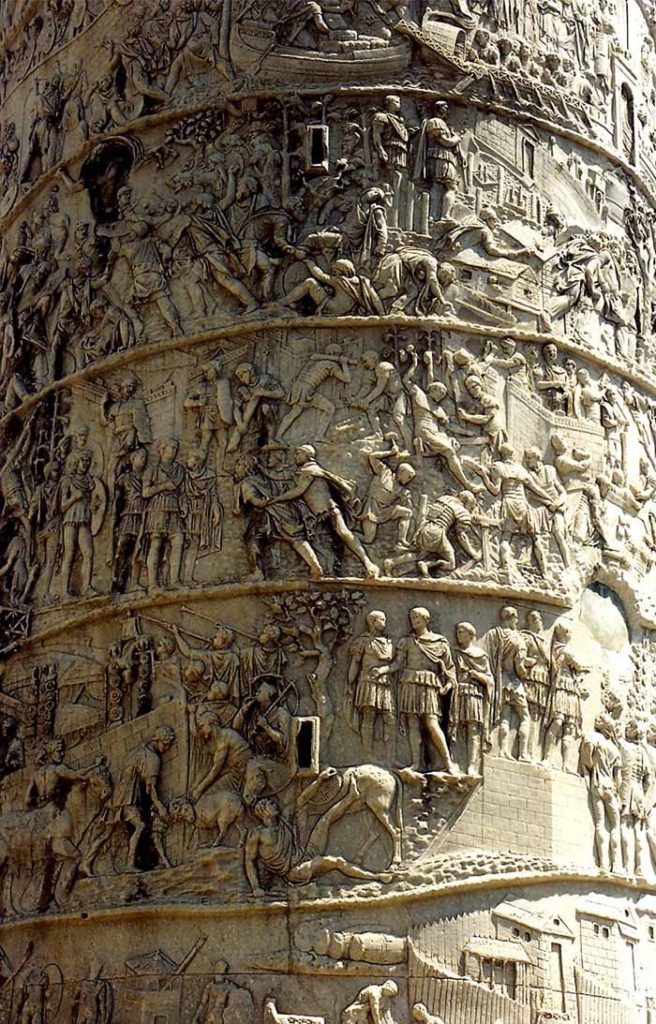

The column of Trajan is one of the most impressive monuments of Roman art and architecture (See Picture 1 of Illustrations). It attracted my attention by its size and superb marble carvings containing a lot of historical information. Another consideration which defined my choice was the almost perfect state of preservation of this antique masterpiece. In the process of my research, I discovered that the purpose of the internal stairway and even the destination of the unprecedented relief frieze winding around the column remain still unclear and disputable. After careful study of high quality photos, drawings, plans and schemes of this unique structure as well as after acquaintance with numerous works and comments by experts and scholars devoted to this antique wonder I formed my own opinion of the famous monument. In the present essay, detailed description of the column of Trajan and analysis of its particularities will be followed by my suppositions and conclusions.

The monument consists of three main parts: the base, the column itself and the statue on its pedestal. The statue representing St. Peter and the pedestal were placed on the top of the column in 1588, on the order of Pope Sixtus V. Originally the monument was crowned with 6 meters high bronze gilded statue of Trajan which is lost with its pedestal. The column is made of 20 huge cylindrical blocks of white Luna (Carrara) marble. Their diameter gradually diminishes from 3.67 m at the bottom to 3.16 m at the top, their height is about 1.5 m and weight varies from 29 to 33 tons. One block capital of the Doric order is weighing 56 tons. To put it in place, builders had to lift it at 35 meters above the ground which was a real technical feat for Antiquity. Splendid narrative spiral relief frieze winding from left to right makes 23 tours around the shaft of the column covering its entire surface. The relief is very low and does not distort the counters of the column. Its contents and purpose will be considered later. The bottom of the shaft is shaped as a huge wreath of beribboned bay-leaves. Inside the column shaft from bottom to top a narrow (0.7 m) spiral stairway of 185 steps is winding from left to right. It is illuminated at regular intervals by 43 slit windows measuring at the outside edge 19 cm. x 5cm. Sections of this staircase had been cut into each of cylindrical blocks of the shaft before it was hoisted in place. After highly precise assembly of the blocks, separate sections formed a perfect stairway which is usable even today. The total height of the column itself is 100 Roman feet or 29.7 meters.

The base of the monument is a cube with the side of 6.18 m made of eight rectangular blocks of the same white Luna marble (See Picture 2). The cornice of the base is crowned at the corners with four eagles (two are still in place) holding in their talons the ends of oak-leaf garlands. From the cornice downwards the surface of the base is covered with reliefs representing war trophies (shields, weapons, helmets, armors) taken from defeated Dacians. Above the doorway, on the south-east side of the base, the dedicatory inscription supported by two winged Victories is located. Inside the base, in a funerary chamber on a special marble shelf, two golden urns containing the ashes of Trajan and of his wife Plotina were originally installed. Not only the urns but even the shelf did not survive to our days. The height of the column with base attains 39 meters. The total weight of the monument is around 1100 tons.

The above mentioned dedicatory inscription on the base of the monument (See Picture 3) informs that it was erected by the Senate and People of Rome in honor of the emperor Trajan whose official titles correspond to the period from 10.12.112 AD to 09.12.113 AD. Unfortunately, the final portion of the inscription is seriously damaged and remains unclear, but we know already by whom and when the column was dedicated. It was done by the emperor in person in 113. In such a way, next year, the 1900th anniversary of the famous monument will be celebrated.

The name of Trajan and the date of construction put the column in historical context permitting to judge about its purpose and meaning.

Marcus Ulpius Traianus was the first emperor born outside Rome (in Spain), from his young age he served in the army and became with time a brilliant military commander highly respected by his troops and civil population. In 97 AD, this promising general was adopted by elderly emperor Nerva and next year became his legal successor. Thanks to his military talents, Trajan expanded his empire beyond the Danube. His conquest of Dacia (the territory of modern Romania) in 106 AD provided him with necessary means for ambitious construction projects such as the harbor of Ostia, Trajan’s Markets, Baths and Forum in Rome. The Senate appreciated the merits and virtues of the emperor by the title of Optimus Princeps under which Trajan remained in Roman history.

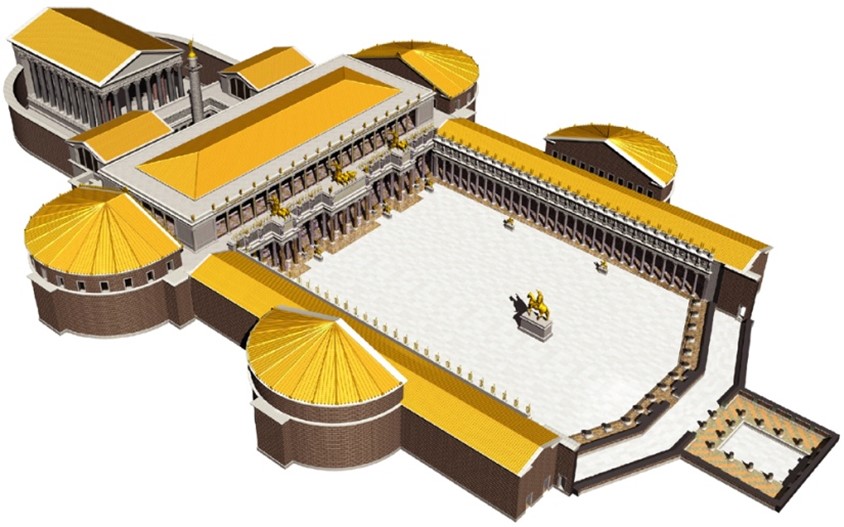

According to the latest researches the majestic column of Trajan which is standing today in the middle of a large square, originally was an integral part of the Forum of Trajan (the largest and the most splendid imperial forum ever created in Rome) and occupied a relatively small courtyard formed by the rear wall of the Basilica Ulpia (considered as one the most magnificent examples of Roman architecture and built of marble of different colors), two libraries (one of them contained Greek texts and other Latin ones) and the Temple of Divine Trajan (See Picture 4). The entire complex of the Forum was designed by Apollodorus of Damascus (See bust on Picture 5), an outstanding architect and talented military engineer, who accompanied Optimus Princeps in his Dacian campaigns and built for his army an impressive bridge on stone pillars across the Danube. He was also the author of Markets and Baths of Trajan in Rome. In his projects, Apollodorus skillfully combined traditional building materials like natural stone and timber with bricks and concrete. Most probably our unprecedented column was also the product of his prolific genius.

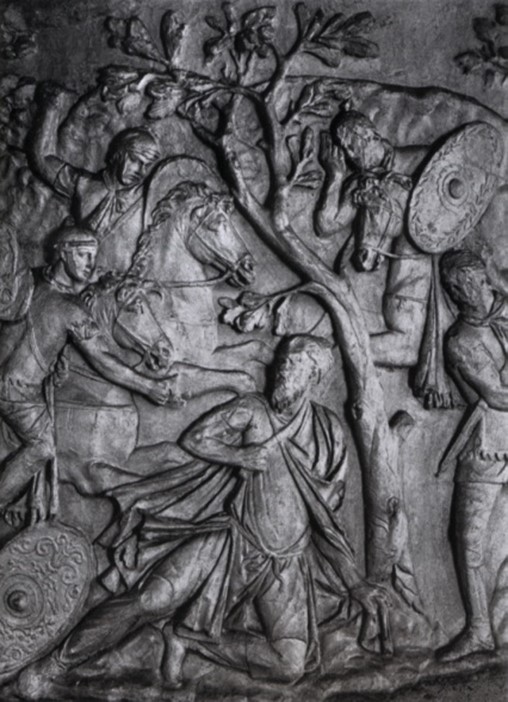

The most striking feature of Trajan’s column is doubtlessly its 200 m long relief frieze winding 23 times around it (See Picture 6). The experts determined that it was chiselled after the column was erected starting from its bottom to the top. The width of the relief band is irregular, upper spirals are noticeably wider than lower ones. Systematic studies of the frieze started in the 19th century, to examine the masterpiece in detail first plaster casts and later high resolution photos of it were made. Thanks to this tremendous work, today we can admire and analyse every one of 155 scenes forming the frieze. Scenes are wittily separated from each other by dividers in the form of trees, mounting ridges or protective walls. Some 2500 figures are shown in this epic narrative. The frieze depicts two Dacian Wars: the first (101-102 AD) consists of three distinctive campaigns illustrated by 77 scenes and the second (105-106 AD) includes two campaigns covered by 76 scenes. Scene 78[1] symbolizing the end of the first War represents winged Victory writing on a shield placed on some support; on both sides the goddess is flanked by trophies taken from Dacians (See Picture 7). Out of 155 scenes only 20 are depicting real fighting in the form of battles, attacks and assaults of fortifications. The frieze is mostly showing Trajan’s troops staying guard, delivering supplies, marching or building bridges, roads and protective walls. Successful completion of the first war is perfectly represented by scene 75 illustrating surrender and submission of humiliated Dacian ruler Decebalus and of his dispirited troops. The second war ended by complete occupation of Dacia, seizure and looting of its capital Sarmizegetusa as well as by suicide of Decebalus (scene 133 – see Picture 8) and his most faithful supporters (Scene 129). Later, Dacia was transformed into a new Roman province. The frieze, obviously, represents real historical events. And this representation is strikingly vivid, detailed and meticulous.

Trajan as the protagonist of this heroic epopee appears not less than 60 times on the frieze; his energetic face and imposing stature (slightly bigger than other participants but not superhuman) are easily recognizable (See Picture 9). He is continuously in command and dominates every situation. Obviously, the main task of the authors of the frieze was to show the leading role as well as virtues and merits of Optimus Princeps. He is very pious and at the beginning of every campaign makes public sacrifices; we should not forget Trajan’s function of Pontifex Maximus. He is prudent and vigilant, that’s why mounted scouts always precede his marching legionaries. The frieze perfectly explains Trajan’s military strategy which consists in creation of extensive network of forts and fortified military camps providing efficient control of the enemy territory. Successful advance of his troops is always ensured by construction of such necessary infrastructures like roads and bridges; all surrounding forests which can be used by hostile natives for ambushes are carefully cut. That’s why Trajan’s legionaries are often represented as skillful builders and woodcutters. Strangely, Roman auxiliary troops never participate in such labours but they always precede heavy armed legionaries in all skirmishes and attacks. Seemingly, Trajan, as an experienced commander, prefers to spare his elite warriors for special occasions.

For historians, the frieze became an inexhaustible source of information: the relief is performed so meticulously that the slightest details of dresses, weapons, shields, helmets, protective armor, military insignia, and defensive works can be distinguished. Different corps of Roman infantry and cavalry are shown in action demonstrating various tactics, for instance, Scene 70 represents close formation of legionaries called turtle in which large shields held by warriors over their heads provide efficient protection against enemy projectiles (See Picture 10). Roman and Dacian civil and military architecture and building techniques are also widely represented on the frieze. Scene 92, for instance, shows ceremonial opening by Trajan of the splendid bridge over the Danube created by Apollodorus of Damascus (See picture 11). Huge stone pillars and complicated wooden upper structure of the bridge are clearly visible. The author of the project is also present at the ceremony; Apollodorus of Damascus was identified thanks to his well attributed busts. On scene 37 we can see a Roman military hospital where a legionary and a auxiliary trooper are treated (See Picture 12). Roman naval architecture, shipping, boating and river crossing are also well represented on the frieze (for instance scenes 31 and 79).

The chiseled narrative provides a lot of information about Dacians: all their warriors are represented bearded and longhaired, they have no helmets or protective armor, their shields are oval. Dacians are wearing long flowing clothes and wide pants, the heads of the upper class representatives are covered with caps. Trajan’s opponents are not so barbarous: they are well armed and their towns and cities are heavily fortified, for instance, their capital Sarmizegetuza resisted not less than three Roman assaults represented in scenes 105, 107 and 109. Dacians are proud and freedom loving: many of them do not accept defeat and prefer death to slavery committing suicide like their ruler Decebalus (scene 133). Today, the frieze is considered as a valuable historical document which in combination with scarce and incomplete written sources permits to re-establish the entire course of Trajan’s campaigns.

Art historians believe that the very idea of narrative frieze derives from the tradition of creating large size tableaus representing bloody battles and heroic onslaughts which were carried by the participants of triumphal processions for demonstration to Roman public. Such paintings are mentioned in particular in descriptions of triumphs of Vespasian and Titus left by Josephus[2]. Trajan’s victories in Dacian Wars were celebrated by two impressive triumphs during which similar tableaus illustrating his campaigns were, most probably, demonstrated to enthusiastic Roman crowd. After the festivities triumphal paintings could be deposited in the libraries of the Forum of Trajan and later reproduced partially or completely by creators of our narrative frieze.

Some scholars recognize in the frieze marble reproduction of an illustrated scroll (rotulus). Such scrolls painted on papyrus, vellum (calfskin) and parchment (lambskin) were popular in Rome. This antique version of modern cartoons most probably also used a sequence of separate scenes to depict the course of events. Unfortunately, Roman illustrated scrolls and books could not survive to our days. But some of them undoubtedly reached the Middle Ages and their tradition of depicting historical events in concise form was preserved and developed by illustrators of medieval chronicles and religious works. The best example of medieval pictorial narrative is the famous Tapestry of Bayeux describing Norman Conquest of England in the 11th century (See Picture 18). In my opinion some scenes of the chiselled frieze clearly remind by their conventionality (when a group of warriors represent the entire battle) of the pictures from medieval chronicles which inevitably inherited some features of Roman illustrated scrolls and books.

Many experts consider the column of Trajan as the first example of purely Roman art. Its size and design are unprecedented for a funeral monument on the one hand and its relief frieze is performed in realistic manner truly representing concrete historical events on the other. The narrative is almost free from allegories so characteristic for Hellenistic art, only on three occasions deities are shown. The very idea of a spiral frieze on a column seems original and innovative. Apollodorus’s creation inspired numerous imitations. In ancient Rome can be mentioned the Column of Antoninus Pius erected in 161 AD (it was only 15 m high and 1.9 m in diameter, made of red granite without any reliefs) and the Column of Marcus Aurelius (176-190 AD) (made of marble, almost 40 m high, with spiral carved frieze it looks almost like a copy of Trajan’s monument)(See Picture 15). Among the latest imitations should be named the bronze Vendome column in Paris (See Picture 16) and Nelson’s column in London (See Picture 17).

In general, the reliefs of the column are very expressive and dynamic; they perfectly convey the idea of invincibility of Trajan and his army. The scenes are realistic and truly reproduce human anatomy (muscles are perfectly shown), movements, gestures and emotions. The presentation is highly artistic and the hand of experienced sculptors is clearly felt. Nevertheless, often the perspective is not observed: the figures in the foreground and in the background are of the same size. Representation of landscape components such as mountains, rivers and forests is forcibly conventional.

Most probably, the narrative frieze is an illustrated version of Trajan’s commentary on his victorious campaigns – the so called Dacica. Unfortunately, only a very small fragment of this work survived to our days. In my opinion, the composition of the frieze was initially designed and developed by Apollodorus of Damascus with following approval by Trajan in person. Reliefs were performed by a team of highly skilled sculptors and judging by the appalling amount of chiseling this work took not less than three years. It is believed that the frieze was brightly painted and that some wooden or metallic inserts reproducing different weapons were fixed in small holes drilled in the hands of many figures. Completed marble narrative was certainly subject of acceptance by both its designer and its sponsor. In spite of dedicatory inscription telling that the column was erected by the Senate and People of Rome, Trajan, most probably, ordered and paid himself his funeral monument.

The main problem for scholars trying to interpret the meaning of the column is inadequate visibility of the narrative frieze. From the ground the viewer cannot see more than six tours of the chiseled spiral; even if the buildings surrounding the column in antiquity had balconies or terraces, from their level the upper portion of the column remained practically invisible. Moreover, to read the spiral narrative, the spectator has to make tours around the monument seeing only one side of it at a time. Another factor reducing the visibility of the frieze was the proximity of wide and high building of Basilica Ulpia towering to the south-east of the column and shading on sunny days considerable part of the monument.

What was the need to create this marble masterpiece which cannot be neither read nor appreciated by the public? In my opinion, there is only one logical answer to this question: the frieze was not intended for the eyes of mortals. My guess is that the cubic base of the monument represents an altar from which a high column of sacrificial smoke swirling in tough spirals slowly rises to the sky (See Picture 13). It is bringing to heaven an unprecedented offering made by Emperor Trajan to the gods of Roman pantheon – his best achievement, his victorious Dacian Wars which made his name famous. The same sacrificial smoke forms a stairway for ascension to the sky of Optimus Princeps, for his apotheosis. And Trajan’s bronze guilt statue shining on the top of the column shows that Roman deities favorably accepted the generous sacrifice of Pontifex Maximus and admitted him to their family. In such a way, the relief frieze was offered to all-seeing gods and to please them no efforts and no means were spared. What kind of narrative could please Roman deities? At first approximation, it should be complete, clear, picturesque and well performed, our marble frieze meets all these requirements. The internal stairway was devised exclusively for Trajan’s consecration and nobody else was allowed to use it. It seems appropriate to add to this that from all the slit windows of the staircase only the sky – the final destination of the regal climber can be seen. It is not difficult to imagine the solemn ceremony in which Trajan takes the stairs to the top of the column where he removes some draperies covering his gilded statue opening it to rapturous looks of Roman public assisting at the transformation of their beloved Optimus Princeps into a new deity. Officially, Roman emperors were deified after their death by special decision of the Senate in the process of religious ritual called consecratio which included cremation of the dead body and liberation of an eagle (sacred bird of Jupiter) intended to bring the regal soul to heaven. Trajan was also consecrated in 117 AD, but it is difficult to say at what moment his soul reached Roman pantheon because he died and was cremated in Cilicia (territory of modern Turkey) and his ashes were brought to Rome by his wife Plotina.

Optimus Princeps inaugurated his funeral monument in 113 AD at the age of about sixty on the eve of his departure to a dangerous military campaign in Parthia. In this connection, the supposition that our huge column of spiraling smoke is rising from Trajan’s funeral pyre is not out of place. This experienced and prudent military commander was accustomed to prepare everything in advance. It is believed that even the Temple of Divine Trajan was built by Apollodorus of Damascus before the monument itself. By the way, if my guess is correct the use of white Luna marble created full impression of billowing white smoke (See Picture 14) and there was no need to paint the narrative frieze. But at the same time, it is easy to admit that Roman gods like humans preferred multicolor sacrificial smokes. It is also quite probable that Trajan in his role of Pontifex Maximus ordered his wonderful marble offering not only to ensure his future apotheosis but to obtain heavenly support for his forthcoming campaign against Parthia. It should be recognized that Optimus Princeps was lucky in his perilous military expedition: in 114-115 AD he conquered Armenia and defeated Parthians, in 116 AD he won Assyria and Babylon. Trajan was the first and the only Roman ruler to reach with his army the Persian Gulf. In 117 AD, he was granted posthumous triumph and the honorary title Parthian was added to his name. The same year, his ashes in a golden urn were deposited at a special marble shelf in the funerary chamber of Trajan’s column. In 122 AD, the ashes of his wife Plotina in a similar urn took their place on the same shelf.

In

conclusion, it is necessary to stress that the column of Trajan is a unique

example of Roman art. This funeral monumentum

represents the apotheosis of Optimus

Princeps ensured through offering of his Dacian victories to the pantheon

of Roman deities. This offering is rising to the sky in the form a column of

white (or colorful) sacrificial smoke bearing on its spirals complete

description of the first (101-102 AD) and the second (105-106 AD) Dacian Wars. This

description represents a superb 200 meters long relief frieze covering the

entire surface of the column’s shaft. The frieze performed with striking

accuracy and thoroughness reproduces real historical events. Thanks to the

above mentioned exclusive features the column of Trajan is a real treasure of

the international cultural heritage.

Picture 1

Picture 2

Picture 3

Picture 4

Picture 5

Picture 6

Picture 7

Picture 8

Picture 9

Picture 10

Picture 11

Picture 12

Picture 13

Picture 14

Picture 15

Picture 16

Picture 17

Picture 18

Bibliography:

1-Lepper, Frank and Frere Sheppard. Trajan’s Column Alan Sutton Publishing, Wolfboro: New Hampshire, USA. 1988.

2-Kleiner, Fred S. A History of Roman Art: Enhanced Edition Wadsworth Cengage Learning , Boston, 2010.

3-Davies, P.J.E., 1997. The Politics of Perpetuation: Trajan’s column and the art of commemoration, American Journal of Archaeology, 101, p. 41-65.

4- Packer, J. E., The Forum of Trajan in Rome, A Study of the Monuments in Brief, University of California Press, Berkeley, California, 2001.

5- Coarelli, Fillipo. The Column of Trajan, Rome, 2000.

6- Beuster, Diana. The column of Trajan – a symbol of the ancient Rome, GRIN Verlag, New York, 2007.

7- Beckmann, Martin. The “Columnae Coc(h)lides” of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius, Phoenix, Autumn – Winter, 2002, vol. 56, no. 3/4, p. 348-357

8- Rossi, Loni. Trajan’s Column and the Dacian Wars, Thames and Hudson, London 1971.

9- Galinier, Martin. La Colonne Trajane et les Forums Impériaux, École Française de Rome Rome, 2007.

10- Depeyrot, Georges. Légions Romaines en Campagne: La Colonne Trajane éditions: Errance Paris, 2008.

Pictures are taken from the following websites:

1. http://www.flickr.com/photos/magistrahf/5944313208/

2. http://cnes.cla.umn.edu/courses/archaeology/Rome/ColumnTrajanFrame.html

3. http://www.flashcardmachine.com/chapter-10fromsevenhillstothreecontinents.html

4. http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/Persons1.htm

5. http://idontunderstandart.wordpress.com/2010/02/10/trajans-column/

6. http://www.digitalsculpture.org/casts/felice/

7. http://www.shunya.net/Pictures/Italia/Rome.htm

8. http://www.roman-empire.net/tours/rome/column-aurelius.html

9. http://www.thefullwiki.org/History_of_Western_typography

10.http://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A4%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB:Roman_turtle_formation_on_trajan_column.jpg

11. https://www2.bc.edu/~greenvac/honors3.html

12. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/customs/questions/london/trafalgar.htm

13. http://www.freemages.fr/browse/photo-1466-colonne-vendome.html

14. http://www.medievalists.net/2012/11/15/new-research-on-how-the-bayeux-tapestry-was-made/